We’re entering the Late Middle Ages (~1300-1500) and on the cusp of the Renaissance...although, Italians ignore the term “Late Middle Ages” altogether and C.S. Lewis argues there was no “Renaissance.” Terms shmerms. It’s the last leg of our journey folks. In all honesty, writing an essay on the fourteenth century seems superfluous in light of Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous Fourteenth Century. I mean, really you should just go read her book. It is exceptional. It’s one of those books that made me fall in love with medieval history. It’s epic, and a bit intimidating, but so worth your time.

Another time-honored option can be found in Johan Huizinga’s The Autumn of the Middle Ages (or The Waning of the Middle Ages) published in 1924. It is a bit outdated and has been debated and critiqued over the years but it’s a fascinating interpretation of the Late Middle Ages.

Many of the sources I read droned on and on about all the atrocities that occurred in the fourteenth century. There were discussions on how the people of the High Middle Ages had grown too comfortable in their progress and believed the horrors of the century were God’s response to humanity’s hubris. Huizinga, the historian I mentioned above, is the classic narrative depicting the ‘death of civilization,’ pointing to decline and disintegration.[1] However, there were also a few sources that highlighted the innovations. They prefer to argue for a more nuanced understanding, emphasizing diversity and complexity. They say medieval civilization didn’t decay, but rather, underwent a metamorphosis.[2] All of these arguments are in light of the “end” of the Middle Ages and the birth of the early modern era ushered in by the Renaissance.

Thus, I began this essay with a list of the top ten crises, but I felt like a bit of a Debby Downer. I will discuss them for sake of historical context, but I also wanted to highlight some of the hope I stumbled upon. There were quite a few rays of light shining through the mire of the sources. I began to see Fate’s efforts to balance the scales. So, while the Rota Fortuna was busy undoing many of the fortunes she had spun in the previous centuries, it wasn’t all doom and gloom.

“All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.” - Julian of Norwich

SETTING THE SCENE

“The political, economic, and cultural advances of the preceding two centuries, the greatest since the fall of the Roman Empire, contributed not merely to a sense of satisfaction but to confidence in the future.”[3] It seems we’re off to a good start. Maybe?

CRISES OF THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

Several drastic events led to the halt of the growth and prosperity we saw in the previous centuries. There was the end of the Medieval Warm Period, which I’ve mentioned in previous essays and the ushering in of what is now known as “The Little Ice Age.” Between 1275 and 1300, a period of multiple volcanic eruptions led to a drop in temperatures. This led to several seasons of intense rainfall and harsh winters which led to failed harvests. This led into the Great Famine that lasted from 1315-1317. Then in 1318, a virulent disease called Rinderpest (aka the Cattle Plague), spread like wildfire through all of Europe, killing “sixty percent of the livestock in any give place.”[4]

As if that wasn’t enough, then the infamous Black Death showed up. Starting in Central Asia during the mid-1340s and quickly spreading to western Europe. It killed over half of all who were infected, most dying within three days. We now know it was the bubonic plague which caused ‘buboes’ that became painfully swollen, then hit the nervous system or respiratory system depending on the strain. A Sienese chronicler said, “They died almost immediately; they would swell up under the armpits and in the groin and drop dead while talking.”[5]

They didn’t know about bacteria and viruses back then. People believed the cause was either God’s punishment, a theory of miasma, or sought an astrological explanation. Those who believed it was punishment chose to live a life of abstinence of everything, hoping that would save them. A new piety arose. Flagellants took to the streets, marching and whipping themselves in an attempt to atone for the sins of mankind and appease God. Others poopoo’d this idea and swung to the opposite side of the pendulum, throwing caution to the wind, choosing to drink and revel themselves through the hellish reality or at least go out joyously. Miasma was the “corruption or pollution of the air by noxious vapors containing poisonous elements caused by rotting, putrid matter and spread by the wind.”[6] People inhaled it, or it was absorbed through the pores of the skin. Thus, many people began isolating and avoiding others. People abandoned their families. Those who could, fled the cities in search of safety in more rural, less populated areas. As for the astrological explanation, King Philip VI of France ordered the medical faculty of the University of Paris to produce a report on the causes and remedies. They concluded, “there was a conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter and Mars in the House of Aquarius. This was extremely potent with regard to the rise of epidemic disease because the conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter gave rise to death and disaster.”[7] Who knew!?

The effects of the Black Death were numerous, as you can imagine. “It was the most disastrous epidemic in the history of humankind with huge historical repercussions and numerous ramifications, which affected the development of western society.”[8] A great medieval primary source to read in regards to the Black Death is Giovanni Bocaccio’s Decameron. It’s a story of several young men and women who fled the crowded streets of Florence to a secluded villa in the countryside to avoid the Black Death. While they waited out the horrors occurring elsewhere, they spent their days telling stories, dancing, singing, and playing games.

“In the year then of our Lord 1348, there happened at Florence, the finest city in all Italy, a most terrible plague; which, whether owing to the influence of the planets, or that it was sent from God as a just punishment for our sins, had broken out some years before in the Levant, and after passing from place to place, and making incredible havoc all the way, had now reached the west....Unlike what had been seen in the east, where bleeding from the nose is the fatal prognostic, here there appeared certain tumours in the groin or under the arm-pits, some as big as a small apple, others as an egg; and afterwards purple spots in most parts of the body...What gave the more virulence to this plague, was that, by being communicated from the sick to the hale, it spread daily, like fire when it comes in contact with large masses of combustibles....One instance of this kind I took particular notice of: the rags of a poor man just dead had been thrown into the street; two hogs came up, and after rooting amongst the rags, and shaking them about in their mouths, in less than an hour they both turned round and died on the spot.”(excerpts from The Decameron)

The Hundred Years War between England and France also occurred this century, starting in 1337 when the French King Charles IV died without a male heir, King Edward III (of England) stubbornly decided he had the right to the French crown and did whatever necessary in his attempts to grab it. This plunged both France and England into war that caused catastrophic devastation and hardship. This is obviously a gross oversimplification; you could build a career discussing the Hundred Years War (some scholars do). There are many fantastic sources if you want to dive deeper. A medieval primary source to look into would be Jean Froissart’s Chroniques. A few nonfiction authors to look into are Edouard Perroy, Christopher Allmand, Jonathan Sumption, Anne Curry, and David Green. Some fiction options to read would be Bernard Cornwell and Dan Jones...there are plenty more, these are the two I’ve read and love.

Rebellions and uprisings increased in England, Italy, Flanders, and Normandy.[9] The famous Peasant’s Revolt occurred in 1381 when people rose up in response to excessive taxes. Wat Tyler and John Ball led thousands into London where they raided, murdered, and burned the city. Even the Byzantine Empire saw drastic changes with the Ottoman Turks moving in and taking over most of the Balkan Peninsula, even setting their sights on the great Constantinople. The Ottoman Empire “rose quickly over the course of the century, began colonizing conquered territories and assimilating people.”[10]

Another big upset of the century was in the symbiotic relationship between the Church and secular rulers. Pope Boniface VIII had issued a bull in 1296 stating that secular rulers could not tax clergy, which ruffled the feathers of Edward I of England and Philip IV of France. But then in 1302, he issued another bull that said, “it is entirely necessary for salvation that all human creation be subject to the pope of Rome.”[11] This was too much (not surprisingly). King Philip IV sent someone to arrest Pope Boniface. He was unsuccessful with the arrest, but the whole affair was so much that Boniface died of shock shortly after. Thus, a secular ruler inadvertently caused the death of a pope. This could be interpreted as an ominous foreshadowing of what was to come in this tenuous relationship.

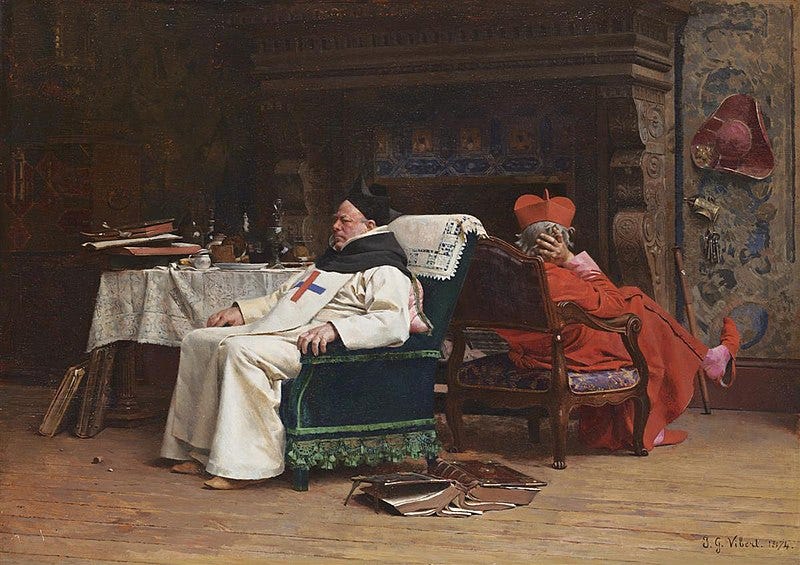

In 1309, Pope Clement V (essentially elected as pope by the forceful hand of King Philip IV of France) decided to establish a new home for the papacy in Avignon, France. This Avignon Papacy spent the next sixty-seven years growing into its apex of administrative and fiscal efficiency.[12] All popes at this time were French. In 1376, Pope Gregory XI moved the Holy See back to Rome. However, when he died two years later, the cardinals elected an Italian pope, Urban VI. Much to their chagrin, he quickly turned into a zealous reformer and began reducing the revenues and influence of the very cardinals who put him in office. The French cardinals didn’t like this, so they fled back to Avignon, cancelled their election of Urban and replaced him with a French pope. Pope Urban responded by electing his own Italian cardinals to replace the French ones who had fled. Excommunications were hurled back and forth between Rome and Avignon, forcing secular rulers to choose sides. This started the “Great Schism.” As you can imagine this led to a rise in criticism of the papacy.

ON THE BRIGHTER SIDE

“He said not: Thou shalt not be tempested, thou shall not be travailed, thou shall not be afflicted; but He said: Thou shalt not be overcome.” (Julian of Norwich)

So far it has all been doom and gloom. But there were also many beautiful things that rose out of the mire. There was “the golden age of monumental architecture in the west, where some of the most iconic buildings in world history were erected,” such as the great showings of might and wealth seen in castles and the symbols of faith seen in the grand cathedrals and churches.[13] New scientific theories emerged, questioning Aristotelian and medieval world views, departing from existing traditions.[14] New developments in ship construction and navigation, such as the mariner’s compass, changed maritime habits to be more efficient. Mechanical clocks were perfected. “Europeans began to divide the hour into sixty minutes and the minute into sixty seconds. Thus, one of the most characteristic aspects of Western civilization—the preoccupation with exact time measurement—was born.”[15] An Italian named Giotto “liberated art from the dominating influence of Byzantine formalism,” upending the more traditional way of capturing the essence of things with symbolism to painting everyday subjects and human emotions more multidimensionally.[16]

But the beauty I want to highlight this century came in the form of people. There were some phenomenal minds this century. Their works are some of the greatest of the Middle Ages and still influence us today. Hopefully their names are familiar to you: Dante, Chaucer, Petrarch, Boccacio, Christine de Pizan, Julian of Norwich, Meister Eckhart, Catherine of Siena...just to name a few. I’ve included a snapshot of a few of them, explaining why I think they’re worth studying and a list of their own works or works about them. They each contributed to the medieval mindset. Knowing them will help you better know the Late Middle Ages.

The Great Italian Trifecta:

Dante Alighieri – wrote his Divine Comedy, a narrative allegorical poem depicting the soul’s journey through the afterlife. It’s one of the greatest works of literature and it’s a beautiful picture of medieval cosmology and mindset. I can’t wait to do one of my MSRs on it!

Petrarch – was known as the “Father of Humanism” who rejected scholasticism and pursued the classical moralists such as Cicero. He wrote Triumphs, a lyric poem about love, chastity, death, fame, time, and eternity. “It charted the mortal and spiritual course of human life all the way through the afterlife.”[17]

Giovanni Boccaccio – I mentioned him and his wonderful work The Decameron already. Like Petrarch, he was a founder of Renaissance Humanism. He was a brilliant poet who heavily influenced some of the greats that came after him. Two other works to investigate was his collection of women biographies, Concerning Famous Women, and his fantastic collection of myths, Genealogia Deorum Gentilium (On the Genealogy of the Pagan Gods), which was an encyclopedia of sorts...a genealogy of pagan gods with allegorical interpretations.

Geoffrey Chaucer – is most famously known for his Canterbury Tales, one of the greatest poetic works in English. Another of his works to check out is Troilus and Criseyde. Both are worth reading. Chaucer was one of the greatest English poets, his work was immensely influential and a great window into the medieval world of his time.

Christine de Pizan – was a brilliant prolific writer and intellectual of the time...whom also happened to be a woman! She wrote on politics, philosophy, government, ethics, religion, and more. But her most popular work is of course The City of Ladies. My copy says it is her “spirited defence of her sex against medieval misogyny and literary stereotypes...now recognized as one of the most important books in the history of feminism.” She’s worth a read!

The Blessed Mystics:

Meister Eckhart – was one of the first and greatest mystics of the 14th century. A Dominican. He focused on the union of the Divine and his creatures. He taught that humanity’s true goal is utter separation from the world of the senses and absorption into the Divine Unknown.[18] Not surprisingly, he was condemned for heresy by the papacy in Avignon.

Julian of Norwich –wrote the Revelations of Divine Love, where she tells of sixteen visions Jesus gave her while she was seriously ill, thought to have been on her deathbed. She was an anchoress, where she vowed to live a solitary life walled up in a small room. We know little about her...which I think was intentional on her part. But the Revelations are profound and beautiful.

Catherine of Siena – was a major force at the beginning of the Great Schism working tirelessly for peace. She achieved fame and influence through her piety, intellect, and character.[19] She too had mystical visions and wrote extensively.

Honorable Mentions – If you are interested in the writings of Christian mysticism, there are quite a few excellent ones from the 14th century. I would point you to The Cloud of Unknowing (by an anonymous writer), Marguerite Porete’s Mirror of Simple Souls (more 13th century, but close enough), and of course...Margery Kempe’s The Book of Margery Kempe.

AS FAR AS I CAN TELL…

There were a lot of crises, calamities, and suffering this century. In Tuchman’s great book A Distant Mirror, she quotes another who said, “the 14th century was a bad time for humanity.” Lerner states that in 1300, Rome was the capital of the world and Europeans seemed confident about their standing, but by 1400, Rome was merely an outpost of a discredited papal faction and the survivors of the Black Death (a population literally half of what it used to be) were traumatized and exhausted by famine, plague, and war.[20] But Tuchman also points out that when it comes to history, we must keep in mind the events that usually get recorded are the negative ones. And as I’ve mentioned above, there were also quite a few glimmers of beauty, innovation, resilience, and hope. So, was the fourteenth century a chasm of suffering that demarcates the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern era? Or was it something else...something a little less calamitous and more par for the medieval course? What are your thoughts?

RESOURCES & FURTHER READING

Benedictow, Ole J. The Complete History of the Black Death

Bishop, Morris. The Middle Ages

Cantor, Norman. The Civilization of the Middle Ages

Hollister, C. Warren. Medieval Europe: A Short History

Holmes, George. The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe

Jones, Dan. Powers & Thrones: A New History of the Middle Ages

Lerner, Robert. The Age of Adversity: The Fourteenth Century

McKitterick, Rosamund. Atlas of the Medieval World

Sullivan, Donald. “The End of the Middle Ages: Decline, Crisis, or Transformation?” The History Teacher 14, no. 4 (1981): 551–65.

Tuchman, Barbara. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous Century

[1] Sullivan, 553.

[2] Sullivan.

[3] Lerner, 3.

[4] Jones, 454.

[5] Holmes, 264.

[6] Benedictow, 5.

[7] Benedictow, 6.

[8] Benedictow, 4.

[9] Jones, 468.

[10] Holmes, 268.

[11] Lerner, 4-5.

[12] Hollister, 323.

[13] Jones, 430-31.

[14] Lerner, 96.

[15] Lerner, 104.

[16] Lerner, 106.

[17] Jones, 492.

[18] Hollister, 320.

[19] Hollister, 321.

[20] Lerner, 120.