There was quite a bit of brutality this century. It weighed heavily on me as I researched. So much purposefully inflicted suffering. Rather than give an MVP award, I feel like I need to establish a Most Brutal Bully award. Then I’d give said MBB to either the Papacy or the Mongols. I still can’t decide who was nastier. But don’t worry. Be consoled by the words of a beautiful soul whose response to the brutality around him was one of hope and resistance. “All the darkness in the world cannot extinguish the light of a single candle.” St Francis of Assisi was not the only one who responded to all the wrongdoing from the powerful forces of the century. Many pushed back against the corruption and violence. But was it enough to tip the scales?

SETTING THE SCENE

David Abulafia sets the scene well by highlighting expansion as the century’s theme. Expansion of Latin Christendom, economy, population, government, and of course, papal authority. There was even expansion into the west from the Mongols. Dan Jones pointed out expansion through a commercial revolution with new ways of trading and financing business, new markets, and the rise of the merchant class (Jones, 354).

KEY PLAYERS

The main players this century were THE PAPACY and its many opponents (the Holy Roman Emperor—HRE, secular rulers, and well…anyone that remotely threatened their control and influence: pagans, heretics, political enemies, and so on), THE CRUSADES (not a person per se, but the whole enterprise itself transformed considerably and affected many people’s lives), and THE MONGOLS who violently swept onto the scene (eerily reminiscent of another group we discussed almost a thousand years ago, how have we covered that much time and space already?!). Then there were those on the other side straining to keep the scales from tipping too far to one side. These were the secular rulers who pushed against the papacy (Frederick II and King Philip the Fair of France), the Mamluks (who stopped the Mongols in their tracks, retook the Holy Land, and united the fragmented Islamic Empire once again—I’m not claiming whether these were good or bad things, simply that they recalibrated the balance of power) and finally, those discontent with all the greed and power struggles, who moved toward a more humble spiritual life centered around poverty, charitable works, and piety (St Francis of Assisi, the Franciscans, the Dominicans, and other mendicants).

THE PAPACY

If you remember from my previous essay (HERE), the papacy had become a “vast, powerful, and complex institution.” In the first half of the thirteenth century, the papacy’s range reached to an unprecedented extent and “sought to expand and control with a new vigor,” (Watt, 107). This expansion was predominantly done through crusading.

The one who led this charge was Pope Innocent III (1198-1216), “a man of limitless energy, high intellectual capacity, and unusual gifts as a leader and administrator,” (Cantor, 417). Innocent believed “everything in the world was the province of the pope,” and the papacy was commissioned by Christ “to govern not only the universal Church but all the secular world.” He got trigger-happy, declaring crusades on anyone who threatened the papacy’s power and influence. He even turned his weapon internally against other Christians, such as with the Cathars in France. Yes, the Cathars were considered heretics, but it was the first time the papacy had called a crusade on Christians.

Catharism had been around since the 1170s. They called themselves the faithful; holy men and women, known as the perfect, marked off from the rest of the world by an ascetic life (Holmes, 330). They believed human flesh was by nature sinful and they had to escape moral corruption through “a strict doctrine of self-denial: sexual abstinence, vegetarianism, and simplicity,” (Jones, 300). But asceticism alone isn’t heretical. It wasn’t until they declared the Roman Church was a product of the forces of evil and established their own priesthood apart from the Church that the papacy took aim at them. The Albigensian Crusade began in 1208/9. Innocent was joined by King Philip Augustus of France (who also wanted more control in the Southern regions where the Cathars were prevalent and saw the pope’s crusade as an opportunity). They sent Simon de Montfort, a famous crusader, to take care of things (Jones, 302). He and his men slaughtered thousands and confiscated their lands. Some say it was genocide. I read a historical fiction book on the Albigensian Crusade called, The Labyrinth, by Kate Mosse. It was very entertaining.

Pope Innocent also pushed for crusades against pagan Slavs in Northeastern Europe. Knights would be absolved of their sins in exchange for conquering peoples, forcibly converting them, and colonizing new lands in the name of the Church. Innocent was even able to pit secular rulers against each other in the papacy’s interests, such as when he excommunicated King John of England over a dispute surrounding the election of the Archbishop of Canterbury and then encouraged the Capetian rulers of France to invade England. Which they did and which led to John abnegating himself before Innocent and making England one of the pope’s vassals. “No king could withstand for long the will of the papacy,” (Cantor, 423. Pope Gregory IX (1227-1241) was “cut from the same cloth as Innocent III” and was devoted to fighting heresy, converting unbelievers, and making “earthly princes aware that their power was nothing when compared with the papal majesty,” (Jones, 305-6).

It's hard for me to hear of these actions and not be disgusted with the papacy. But of course, it all depends on how you spin it. When reading sources more sympathetic to the Catholic Church, the same actions were described differently. Rather than using the term colonization in Northeastern Europe, they’d say evangelization. Rather than accuse the papacy of declaring crusades on other Christians who threatened their control and influence, they were fighting heretics and dissenters who threatened Christendom. Regardless, some of their corruption and brutality just couldn’t be excused. Even within the Catholic faith, people were growing discontent with the papacy’s avarice. While the popes were busy trying to build papal primacy and “apostolic sovereignty” (Watt, 114) mendicantism was rising in popularity, tipping the scales back toward a semblance of balance.

Mendicantism was made up of religious orders devoted to a life of poverty, preaching, charitable deeds, rejecting the life of the cloister to live in the world, not apart from it. Members were not from aristocracy but from the lower levels of society (Hollister, 208). The order that did the most in terms of balancing the scales was the Franciscan movement, led by Saint Francis of Assisi. “He determined to live as Christ had lived—a mendicant, a teacher, a healer, the friend of all creatures, the preacher of the simplest and the most sublime truths,” (Cantor, 430). He believed profound individual religious experience strengthened your faith. Franciscans wanted to stir people’s hearts through action and example. St. Francis said, “Preach the Gospels every day and only if you have to…use words.” The friars were to have no possessions, wander the countryside preaching and caring for the poor and sick, and to live on alms and charity from the people.

The Dominicans were another such order, but different in that they were more intellectual and scholarly, working to demonstrate the compatibility of faith and science. Their purpose was more informed preaching on truth. A famous Dominican you might have heard of was Thomas Aquinas. I’m conflicted in my opinion of the Dominican Order of the thirteenth century. While their pursuits of truth and reconciling faith and science sound like laudable endeavors, they were also used as the arm of the papacy known to interrogate and condemn potential heretics (they came to be known as the Dominican Inquisition, also Domini canes, “God’s dogs”). So, there’s that little skeleton in their closet. To be fair, many Dominicans resigned, not wanting to participate in the torture and executions. So that’s good. And I believe they do excellent work now.

The papacy was also constantly at odds with secular rulers who wouldn’t relinquish control to them. One of the biggest conflicts was with the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. The papacy appointed Frederick as emperor in the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 but quickly realized their mistake. He was not only HRE, but also king of not one, but two kingdoms: Germany and Sicily. His domains suddenly surrounded the papacy in Italy and threatened their power. Pope Gregory IX was constantly at odds with him, excommunicating him (some say twice, another said four times!), and even declaring war on him in an attempt to gain Sicily for the papacy. The popes became obsessed with the Hohenstaufen threat (Frederick’s family) and decided the whole dynasty needed to be annihilated (Abulafia, 4). But Frederick was not to be manhandled.

Emperor Frederick II was “the most extraordinary ruler of the Middle Ages,” (Bishop, 69). He was nicknamed “the wonder of the world” for his piercing intellect, political genius, and perpetual restlessness,” (Jones, 305). The only HRE to manage a double inheritance, ruling a universal empire and dual monarchies (Abulafia, Frederick: A Medieval Emperor, 2). And in staying true to his reputation, in 1228-9, Frederick frustrated the papacy when he did what no one before him could do…he went on crusade and successfully negotiated a peace treaty, gaining back the holy city of Jerusalem…without spilling a drop of blood!

Frederick II had declared he would go on crusade several times…but had yet to go. His reasons for not going were legitimate. His lands both in Germany and Sicily were constantly being threatened and he was needed at home. When he finally set out, he fell violently ill and was once again deterred. This was too much for Pope Gregory IX (who you will remember had it out for him already). So, Gregory excommunicated Frederick. Take that, secular ruler who won’t bow to my dominance! Frederick wrote a letter attacking the corruption of the papacy, claiming they were wolves in sheep’s clothing (Abulafia, Frederick: A Medieval Emperor, 169). Frederick had no taste for the papacy’s vision of papal power. Once Frederick was well, he continued the crusade anyway, dismissing the pope’s orders not to. This was a big deal. Frederick going on crusade while being excommunicated meant that the crusade wasn’t a papal one, but rather, an imperial one. "The threat of a crusade unblessed by the papacy was a threat to the political standing of the papacy, as organizer of holy war and mediator, through the offer of remission of sins, between God and man," (Abulafia, 170). Take that, pompous religious ruler who cannot have power over me!

Frederick had a previous relationship with Muslim rulers from his rule in Sicily. He already knew the Egyptian sultan al-Kamil and knew the delicacy of diplomatic balance in the Middle East (Abulafia, 171). He traveled to the holy land and peacefully negotiated with al-Kamil where he gained Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Nazareth (the three holiest sites of Christendom) and a safe passageway from the ports to the city. It seems like this harrowing feat should be celebrated through the ages! Yet, due to his excommunication and his power being a threat to the nobility in the Holy Land (they saw him trying to extend his reach into their domains), neither Frederick nor his success was well received. Sometimes you just can’t win.

Even though it seems like a victory, ten years later when the truce Frederick negotiated was over, Jerusalem was attacked by Turks employed by the Egyptians who retook the city. “Thus began six hundred and fifty years of uninterrupted Moslem control of the Holy City,” (Brundage). It’s argued that once Jerusalem fell, the rest of the Latin East followed suit. It was the beginning of the end for the Latin East.

To add insult to injury, even after Frederick II died, the papacy continued to hound his dynasty. Dan Jones wraps up the bitter struggle between to two powerhouses rather well. He says it all ended with Frederick’s grandson, the king of Jerusalem, being captured by papal allies and beheaded. “It would be difficult to think of a greater inversion—or even perversion—of the original mission of crusading than a Latin king of Jerusalem losing his head in a war against the pope,” (Jones, 306). Note: sources more sympathetic to Catholic history vehemently deny that Pope Clement had anything to do with the beheading of Conradin (Frederick’s grandson). Again, history all depends on who’s telling it. Anyway, while Frederick II offered some good wrestling against the strength of the papacy and may have won the battle in the Holy Land, sadly, I feel the papacy won the war. The Hohenstaufen line ended; the papacy had successfully destroyed a monarchy (Cantor, 461). But they had also lost their way, tainted their hands by engaging in an all-out war for mere political power and had lost sight of the original goal of the crusades by perverting them with their greed and brutality against anyone they saw as opponents. So, did they really win? “For what profit is it to a man if he gains the whole world, yet forfeits his soul?” (Matthew 16:26). Just sayin’.

THE MONGOLS

The other bullies of the century were the Mongols. It was a bit of déjà vu, seeing a nomadic group riding in from Asia terrorizing and swiftly conquering all they crossed paths with. Sound familiar? Remember the Huns?

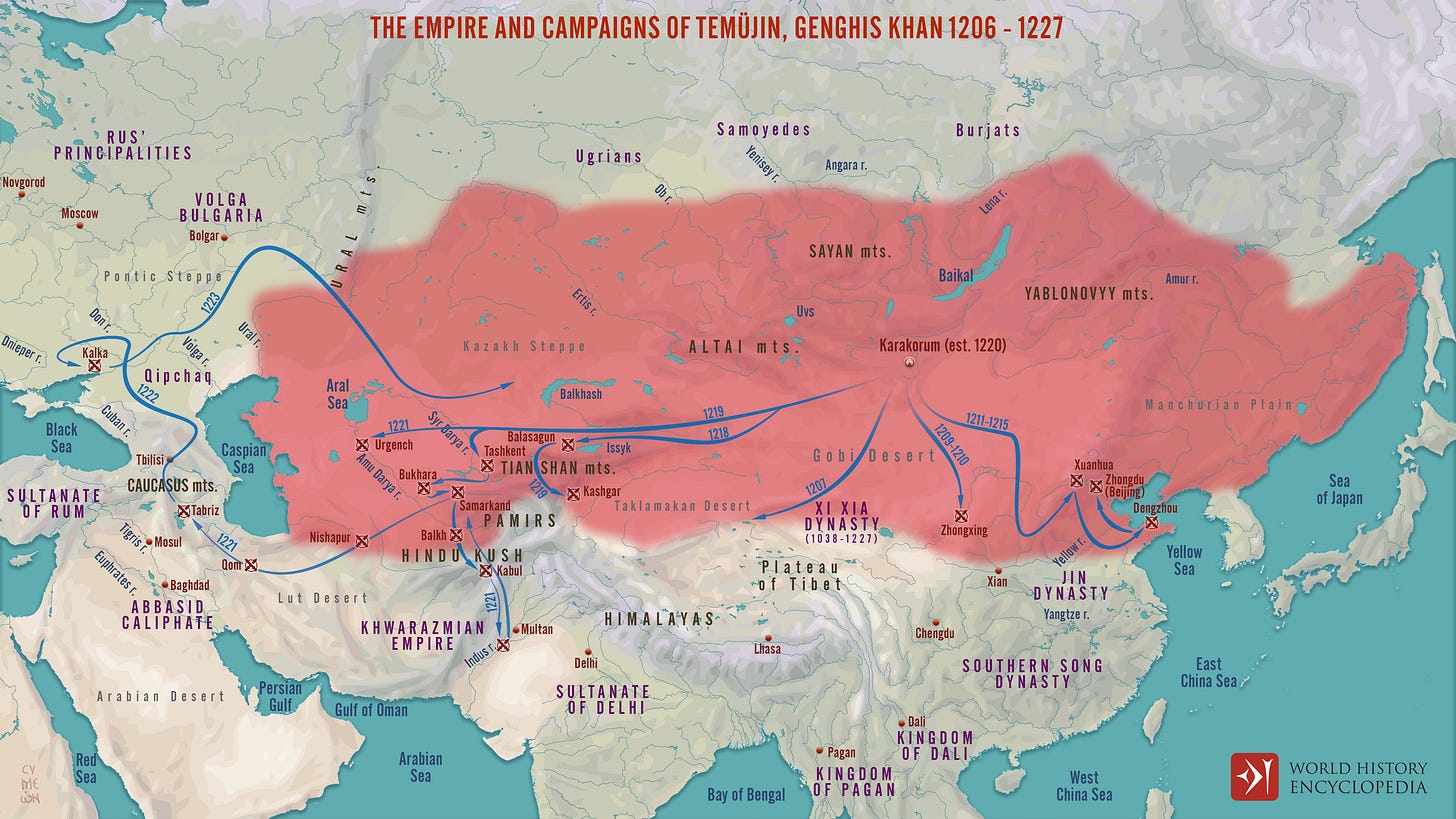

The Mongols arrived in the early 1200s, attacking and destroying states in Asia Minor and Eastern Europe. By mid-century, all the lands of the Rus’ had been brought under Mongol administrative and fiscal control (McKitterick, 206). They leveled cities, burning everything, leaving nothing and no one alive (Jones, 314). They devastated the Islamic world. In 1258, they attacked Baghdad, killing virtually everyone. “All the libraries and schools and hospitals, all of the city’s archives and records, all the artifacts of civilization enshrined there, all the testimonials to the great surge of Islamic civilization in its golden age, perished utterly,” (Ansari, 156). In the destruction of the famous House of Wisdom, “Thousands of treatises and books on philosophy, medicine, astronomy, and much else—which had been translated over centuries from Greek, Syriac, Indian, and Persian languages into Arabic—were thrown into the river Tigris,” (Jones, 335-6). Then they killed the Abbasid caliph, ending the Abbasid dynasty that had started way back in 750CE. They even went and massacred the infamous Assassins in northern Iraq, destroying their stronghold, their records, libraries, and papers. Overall, they killed millions. Whether these numbers are completely accurate or not, they paint a picture of the scale of brutality and the size of massacres they carried out (Ansari, 153). HERE is a good article with more detail.

Adding each newly conquered territory, they built the largest contiguous land empire in the world. They pioneered the administration that goes along with a global empire: a world-class postal system, universal law code, military reform, and efficient metropolitan planning (Jones, 314). They might have been brutal, but then they turned around and brought about an era of peace known as the Pax Mongolica (Jones, 314). This supposed peace opened the way for trade to flourish by connecting the Far East with Western Europe (Jones, 353). “It permitted epic journeys of overland exploration, and an easier transfer between east and west of technologies, knowledge, and people,” (Jones, 314). Out of this came the great medieval traveling literature, the journals and diaries of men such as Marco Polo and quite a few Dominicans and Franciscans who had been sent as envoys and missionaries to the Mongols. I encourage you to read some, it’s fascinating. I’ll include some links below. While the Silk Road became busy with trade and exploration from this Mongol peace, it also brought devastation…which we’ll see next century.

Just like the papacy, the Mongol’s rapid expansion received pushback as well. In 1260, they marched to fight the Muslim Mamluks of Egypt. But they were defeated…for the first time. This was an interesting encounter. If you remember, the Mamluks were originally Turkish slaves who were bought and then raised and trained as soldiers to fight for the Ayyubid dynasty. The two sides were eerily similar in their fighting. Both nomadic peoples from the Steppe prized for their ability with the bow and arrow while fighting on horseback. It seems the Mongols had finally met their match…in a group of people just like them. “The battle brought together two armies, and really two peoples, who fought and lived in similar ways. Steppe nomads and former steppe nomads, trained from youth in the intricacies of mounted archery combat, confronted each other on a battlefield thousands of miles from their ancestral homelands, with the future of the Middle East at stake,” (Lower, 20). The Mamluk general Baybars crushed the Mongols, ending their expansion into Muslim territory. It was a momentous victory. “It destroyed the Mongols’ reputation of invincibility, halted their westward advance toward Egypt and North Africa, conferred prestige on the Mamluk victors, and accelerated the Islamization of the region,” (Lower, 21). This brings us to the Islamic Empire.

After general Baybars defeated the Mongols, he marched into Cairo and took over, ending the Ayyubid’s rule, and establishing the Mamluk dynasty (Ansari, 157). This was a shift in the balance of power within the Islamic Empire, which had been struggling with deep internal fragmentation for the first half of the century. The Ayyubids had used the Mamluks as their elite military unit. It’s a bit ironic the people they enslaved and trained to protect them ended up taking over. It reminds me vaguely of the Mayors of the Palace back in 7th and 8th century Francia who ran things for the Merovingian dynasty, but slowly took over and then became the Carolingian dynasty that replaced them…I love seeing patterns, parallels, and themes in history…but I digress. “Under the Mamluks, Egypt became the leading nation in the Arab world, a status it never really relinquished,” (Ansari, 157). Baybar quickly turned his sights on Syria, which had already been decimated by the Mongols, and united it with Egypt into one realm. He swiftly went from a slave boy to a sultan of a “genuine Near Eastern superpower and a state that would endure into the sixteenth century,” (Lower, 22). He also swept into the Holy Land and took crusader states one by one, starting with Caesarea, Haifa, and Arsuf (1265). Then he took Safad and Galilee (1266), then Jaffa and Beirut and Antioch (1268). And finally, in 1291, the Mamluks took Acre, the last bastion of crusader presence in the Holy Land. “With the fall of Acre and the evacuation of the remaining strongholds and towns, Christian occupation of Outremer was at an end,” (Holmes, 260-1). Which brings us to the Crusades.

THE CRUSADES

I’ve already mentioned them quite a bit so far. But just to tie things up, let’s look at them as a whole over the century. Crusading being a Christian holy war against infidels in the Holy Land was no longer an accurate definition. The concept had evolved. The papacy was declaring crusades in other regions (Spain, Eastern Europe, Italy, France) against other people (heretics, dissenters, pagans, political opponents). Some supposed crusades weren’t even technically sanctioned by the pope (eg the Fourth Crusade, which I wrote about HERE, and Frederick II’s crusade). Crusading had become a weapon that allowed Latin Christendom to violently expand. But sometimes it wasn’t even about Christendom, but more about extending/gaining political power and control.

“Crusading—a bastard hybrid of religion and violence, adopted as a vehicle for papal ambition but eventually allowed to run as it pleased, where it pleased, and against whom it pleased, was one of the Middle Ages’ most successful and enduringly poisonous ideas.” (Jones, 308).

After my class last semester, learning how the concept of crusading drastically changed, and reading so many scholarly arguments on what constituted a crusade— which ones were in or out—I feel like I’ve decided it’s another word that has too much confusion attached to be helpful. Similar to the term feudalism…but again, I digress. I will dive deeper into the Crusades in another essay. But I’d love to hear your thoughts on them.

NOTABLES

There were, yet again, so many things to note, but I’ll mention just a few. These are not to be considered secondary or of less importance than what I’ve discussed above. I just can’t fit it all in! I’ll try to distill things down to a few sentences for each notable.

England this century was all about Magna Carta and the law gaining supremacy over the will of the king. While it failed out of the gate, it did end up affecting the way things worked down the road. So, I’d say it was a pretty significant notable to mention.

The Capetian dynasty rose in power under Louis IX (1226-70) and France arguably became the most important European state of the time (Cantor, 409). After Frederick’s Hohenstaufen dynasty was destroyed, people’s gaze shifted to King Louis. Also, Henry III of England held the duchy of Aquitaine and became a vassal of the French King, which would inevitably lead to war…because, well, how could a ruler who was a king in his own right act as the vassal of another? (Holmes, 219). This is important to note as the beginning of things to come.

By mid-century, most of Spain had been rendered from Muslim control into Christian hands. Muslim Spain then only consisted of Granada. But much of the region remained a place where three diverse populations—Christian, Jewish, and Muslim—coexisted.

McKitterick explains Italy in a way that makes sense to me. Too often when scholars go into detail about Italy, I get confused. Here is what she says…

“There were two Italies in the Middle Ages. In the south a wealthy monarchy, founded by the Norman Roger II in 1130, ruled grain-rich lands inhabited by Greeks, Muslims, Latins, and Jews, and became involved in the politics of the entire Mediterranean. In the north and centre a galaxy of cities dependent on trade, finance, the cloth and metal industries developed republican governments in which local elites shared power,” (McKitterick, 220).

AS FAR AS I CAN TELL…

The papacy had a grand vision of papal sovereignty and their avarice led them to inflict great suffering on a lot of people. They erred in thinking secular rulers would bow to the encroachment into their ruling and affairs. As I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, there were those whose responses to the bullies helped tip the scales back to a semblance of balance. So, kudos to Frederick II for pushing back against Pope Gregory. He might have lost his battle with him, but his resistance, in my opinion, contributed to the papacy’s demise. By the time King Philip IV of France faced off with Pope Boniface VIII in the 1290s, the world had had enough of the papacy’s minatory tyranny. When Boniface intervened in Philip’s rule to tax the clergy in his domains by declaring rulers required the pope’s approval first, Philip parried by attacking the pope’s universal sovereignty, doctrinal orthodoxy, and capacity to undertake inquiries into heresy. Many clergy and bishops sided with the king. Then he sent an army to kidnap the pope from his home in Alagni, Italy. Boniface escaped and fled to Rome where he subsequently died from the shock of the attack. Essentially, Philip was responsible for the demise of Boniface (Holmes, 311).

It wasn’t just secular rulers who resisted the papacy’s rapacity and cupidity. Mendicants, such as the Franciscans, also pushed back. The papacy’s weapon of choice, crusading, was also in decline and the great Latin East was no more.

The Mongols bullied and expanded too, building a vast empire. However, their expansion was halted by the Mamluks, who also unified a fragmented empire and reestablished itself as the boss in the Holy Lands.

So even though the expansion, especially by the papacy and Mongols, was pretty heavy, by the end of the century it seems the scales were able to maintain some semblance of balance. Maybe? What are your thoughts?

RESOURCES & FURTHER READING

Abulafia, David. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 5: c. 1198-c.1300

Abulafia, David. Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor

Ansary, Tamim. Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

Bishop, Morris. The Middle Ages

Brundage, James. The Crusades: A Documentary History

Cantor, Norman. The Civilization of the Middle Ages

Holmes, George. The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe

Jones, Dan. Powers & Thrones: A New History of the Middle Ages

Jones, Dan. The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England

Lowers, Michael. The Tunis Crusade of 1270: A Mediterranean History

McKitterick, Rosamund. Atlas of the Medieval World

Watt, J.A. The Papacy (Ch 5 in The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 5: c. 1198-c.1300)

Medieval Travel Literature: