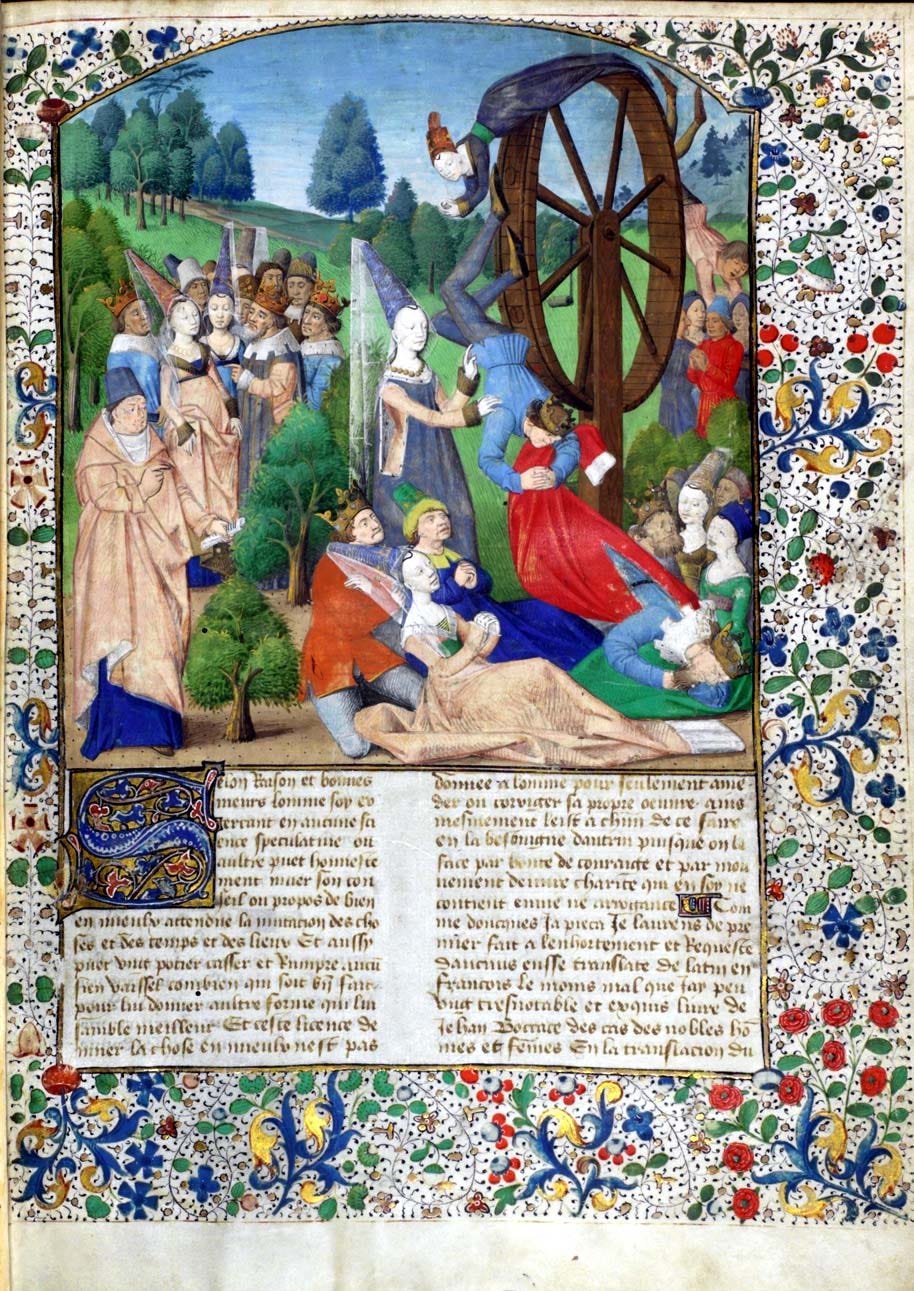

When Boethius wrote about the Goddess Fortune in his Consolatio Philosphiae, he quotes her saying, “Inconstancy is my very essence; it is the game I never cease to play as I turn my wheel in its ever-changing circle, filled with joy as I bring the top to the bottom and the bottom to the top.” I could do an entire post on the Rota Fortunae (Wheel of Fortune) concept and imagery in the Middle Ages. It was everywhere.

SETTING THE SCENE

As we exit the eighth century, we have the seemingly sturdy medieval imperial tripod: Byzantine Empire, Islamic Empire, and Western Christendom. All seemed in a somewhat stable spot. The Carolingians were basking in glory from Charlemagne crowned Holy Roman Emperor, solidifying Western Christendom as its own entity apart from its eastern counterpart. The Islamic Empire was flourishing under the great caliph Harun al-Rashid who had ushered in the Islamic Golden Age. Cordoba in Al-Andalus (what the Muslims called the Iberian Peninsula/Spain) was becoming the western Baghdad. Byzantium had spent most of the previous century fighting Saracens (the Arabs) and the Bulgars. The “scheming and duplicitous” Empress Irene ruled; she had murdered her son to be the sole occupant of the throne (Norwich, p 376). But! They were still holding strong, with Constantinople “by now incontestably the largest city, as well as the richest and most sumptuous, in the world” (Norwich, p 382).

Everything seemed copacetic, right? Never! Cue the new crew rowing onto the scene…the Vikings: a violent barbarous group of bearded men in horned hats intent on nothing but destruction, rape, and pillaging (please read with a tone dripping with sarcasm). The Rota Fortunae was about to spin yet again.

KEY PLAYERS

The most notorious player of the ninth century is the Viking. But we still have the medieval imperial tripod to follow. So, let’s dig in.

THE ISLAMIC EMPIRE

The Islamic Empire grew fragmented. Caliph Harun al-Rashid died in 809 CE. A civil war between his sons broke out and the son of his general Tahir also rose and declared himself ruler of Khorasan, establishing the Tahirids. There were now three Islamic dynasties ruling the once unified empire: the Abbasids, the Tahirids, and the Umayyads in al-Andalus. In 861 CE, some former caliphs mutinied, raised an army, and killed the Abbasid caliph. They became “kingmakers” in a sense and began putting their own men forward as caliphs who would cater to their agendas (Wise, p 455). The latter half of the century saw a long process of political disintegration in areas such as Spain, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, and Eastern Persia.

THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE

The two main happenings in the Byzantine Empire were the resolution of the Iconoclast Heresy (where it was finally decided to rule in favor of icons in 843 CE) and the establishment of the Macedonian dynasty that would rule for the next two centuries and usher in the Golden Age of Byzantium. But it was a reality sh*t show.

In 820 CE, Emperor Leo V was assassinated by his friend and general Michael II, during a Christmas Mass (Michael II had helped Leo gain the throne. But then Leo ordered that Michael be killed. But Michael killed Leo instead and claimed himself emperor). Michael II’s son Theophilos took over in 829 CE. Theophilos’ son Michael III inherited the crown in 842 CE after his father died. This is where it gets crazy…errr, crazier? Michael III had a best friend named Basil. Basil was twenty years older than Michael, yet was his adopted son (I know, I don’t get it either). Michael III named Basil his co-emperor in 866 CE. Michael III had a concubine, Eudokia, who he was told he could no longer have. Michael III married her to his co-emperor/friend/adopted son Basil, so he could keep sleeping with her. But then Basil demanded he needed someone he could sleep with since his wife was sleeping with Michael. So, Michael pulled his sister out of a convent and gave her to Basil. But then Basil murdered Michael III. Basil’s son, from Eudokia, (who was most likely Michael’s son) was crowned emperor in 886 CE (Wise-Bauer, p 447). Thus, the Macedonian dynasty began. I promise I did not make this up.

WESTERN CHRISTENDOM

Western Christendom went through some hard times as well: the Carolingian kingdom crumbled into something that was not part of Charlemagne’s vision, the papacy entered its own ‘dark night of the soul’ wrestling for authority in a new political climate, and of course, the Viking invasions forever changed the dynamics of the map.

Charlemagne died in 814 CE. Known as the “Father of Europe,” he achieved great things in unifying most of Western Europe and starting the Carolingian Renaissance. Sadly, in hindsight, we can see his charisma was a driving force behind his success. This charisma potentially blinded people from the weaknesses of the empire. “Charlemagne’s achievement was one thing, his legacy another. His heir inherited an empty treasury, a corrupt and rebellious following, an ill-knit empire, a countryside often ruled by vendetta, famine-stricken and plague-ridden. Behind the veneer of unity and of uniformity lay a society intensely localized, incapable alike of national and imperial aspirations,” (Wallace-Hadrill, p 121). In 843 CE, after much civil war, Charlemagne’s grandsons gathered at the Treaty of Verdun and partitioned the empire into 3 Carolingian realms: the western, the eastern, and an anomalous Middle Kingdom (Cantor, p 193).

While the Carolingian dynastic men were busy fighting themselves, the wealthy, land-owning aristocracy decided not to depend on the crown and started ruling their lands as sovereigns themselves. Simultaneously,Viking invasions threatened the security of the Franks, pushing people toward the most powerful lord nearby, offering him their loyal service in return for protection. This further entrenched and strengthened these duchies. By 888 CE, the last Carolingian king to unify the empire, Charles the Fat, died and the empire disintegrated into even smaller pieces. By the end of the ninth century, the Carolingian Empire was now just a land with a multitude of duchies and provinces. The Rota Fortunae had spun again.

THE VIKINGS

Vikings first arrived on the scene in 793 CE when they sacked the monastery on Lindisfarne Island off the coast of Britain. Then there are a slew of stories of the hell they wrecked on all Christendom…even down to Constantinople. Patriarch Photius described these attacks saying…

“A nation dwelling somewhere far from our country, barbarous, nomadic, armed with arrogance, unwatched, unchallenged, leaderless, has so suddenly, in the twinkling of an eye, like a wave of the sea, poured over our frontiers, and as a wild boar has devoured the inhabitants of the land like grass, or straw, or a crop (O, the God-sent punishment that befell us!), sparing nothing from man to beast, not respecting female weakness, not pitying tender infants, not reverencing the hoary hairs of old men, softened by nothing that is wont to move human nature to pity…but boldly thrusting their sword through persons of every age and sex.” (Wise-Bauer, p 435).

Let’s keep in mind that dear ole Photius was a Christian man, describing an army of pagans. So there’s a bit of a hell and damnation flare going on. Not to diminish the terror and destruction that happened but let’s try and get to the bottom of who these pitiless, barbarous heathens were.

Beginning in 800 CE there was the Medieval Climactic Anomaly…essentially a warm period. Temperatures in Europe began to rise by a few degrees, melting ice from the Northern Sea routes (Wise-Bauer, p 431). Vikings then began sailing down from the north to raid and pillage, attacking Britain, France, Spain, and the Mediterranean coasts, even Alexandria! Why did they do this? Some say it was due to problems back home in Scandinavia, things such as population growth, poor agricultural land, political disputes, and a lack of marriageable women (Jarman, p 15). From their perspective, they were sea-faring heroes returning home with wealth and treasures. They weren’t identifying themselves as barbarous pagans (Hindley, p 180). These attacks were initially for plunder but slowly changed into plans of conquest and settlement.

They were intelligent businessmen and good farmers (Wallace-Hadrill, p 135). Some took control of the wine industry off the rivers in Francia, some made their way towards the port of Derbent on the Caspian Sea, where they traded with Khazar and Muslim merchants (Wise-Bauer, p 433).

It’s also important to note the term Viking encompasses a lot of different peoples:

The Swedes took the Baltic route, up the German and Russian rivers where their trading post at Kiev could reach Byzantium (Wallace-Hadrill, p 134). The Swedes established Novgorod, ruling over the Slavic peoples. A man called Rurik led some of the Rus to take Kiev and founded a princedom that a century later would be the most powerful in Russia (Holmes, p 114).

The Norwegians raided around Scotland and Ireland, then on to Iceland and Greenland, and even to North America in Newfoundland. They settled Iceland circa 870 CE.

The Danes focused on Anglo-Saxon Britain and the continent. By the 850s, they began overwintering in England rather than returning home. In 865 CE, the Great Army first appeared in England and over the next 13 years would move across the country, eventually capturing York in 866 CE and East Anglia in 868 CE. By the 880s, around half of England was under Scandinavian control or direct rule (Jones, p 182).

So, while Hollywood depicts them as barbaric violent warriors who raped, pillaged, and murdered…harbingers of doom and destruction…that’s not the entire story. They were also skilled traders, farmers, and craftsmen. They built large cultural and commercial networks across Europe that connected a map previously localized and insular. By the end of the ninth century, they still had Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, but also had new kingdoms in Ireland, the Orkneys, settlements in Francia, and a profitable trading community in Kievan Rus and Novgorod. Some even say the Vikings led to the unification of England.

Without their threat, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms would not have come together to combat them. Holmes says, “It is difficult to imagine how England could have emerged by the late tenth century as a wealthy, powerful, and United Kingdom had not the Vikings destroyed all native dynasties except that of the West Saxons. The English nation was, in a sense, created by the Vikings, with the help of the West Saxon propagandists,” (Homes, p 114). The Vikings devastated England. The merchant centers diminished almost to extinction and many of the great churches disappeared (Kindly, p 178). By 860 CE, Mercia had declined in power, Wessex had ascended, annexing both Kent and Sussex, and the southeast of England was more or less united under a single throne. And then King Alfred took the thrown in 871 CE.

In 878 CE, Alfred faced the Great Army at Edington and won (Wise-Bauer, p 464). The Viking chief Guthrum signed a treaty with Alfred, converting himself and thirty of his warriors to Christianity. The Treaty of Wedmore divided England into two: the Anglo-Saxons and Danelaw. Alfred eventually took back London and most of South and Southwest England. He systematized the military, built a navy, fortified garrisoned towns, issued law reforms, and brought scholars from everywhere to translate Classical Latin works into Anglo-Saxon. The famous Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was created around this time as well.

NOTABLES

Something to note from this century was the transition from a centralized government built around the throne back to an insular, localized, and rural way of life. The medieval manor was the basic unit of the economic system. It was a self-sufficient system. International trade still existed (as we saw with the Vikings) but used only by the wealthy. Most people’s lives centered around the manor where the lord had land divided into strips. The peasant serfs were given strips of land for themselves in exchange for also working the lord’s land. They were bound to the land and subject to duties imposed by the lord, such as taxes and military service.

FEUDALISM

And this is where we talk about feudalism. Because you can’t discuss the Middle Ages without hearing the term. It’s a hot topic because some scholars argue it wasn’t even a thing (look up Susan Reynolds, if you’re interested) and it wasn’t until later down the road that the term was coined. Now it’s so watered down with different meanings that you can’t define it, let alone accurately assign it to a specific medieval system or community. A basic oversimplified way to explain it is “the exchange of service, on the part of the poor, for protection and provision from the rich,” (Wise-Bauer, p 547).

One school defines feudalism as a system of decentralized government, “public power in private hands” that came about in the second half of the ninth century in response to the disintegration of the Carolingian Empire (Cantor, p 195). It was a system of legal and political relationships involving free men (different from manorialism which was an agrarian system involving dependent peasants).

The second school defines it not just in political and legal terms, but saw it as a way of life, a whole system including political, economic, ecclesiastical, and cultural. And it was all centered around lordship, where most of the power was in the hands of the nobility (Cantor, p 196). These aristocratic nobles turned from the crown and established their own hereditary fiefdoms.

It’s an ongoing debate and there is a lot of literature on it. An essential treatise on it is Susan Reynolds’ Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted, (Oxford University Press, 1994). Another excellent article is “The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe,” by Elizabeth A. R. Brown.

AS FAR AS I CAN TELL…

The Rota Fortunae was busy in the ninth century. Those who were at the top in 800 CE had wheeled around to the bottom by 900 CE. The Carolingian Empire fell as quickly as it rose. The symbiotic relationship between the papacy and the crown weakened when the political climate shifted in favor of localism, feudalism (if it existed), and the nobility calling the shots. The Islamic empire was divided between multiple dynasties establishing their own caliphs and centers of power.

But the Vikings had risen from relative obscurity to establishing kingdoms all over the European map. And a new dawn had risen on the dark ages of the isle of Britain. The Anglo-Saxons were led by Alfred the Great, whose kingdom of Wessex was the only one to have survived the Viking onslaught (Wickham, p 456). He worked toward unification as “’the king of the Anglo-Saxons’, or, in the Chronicle’s words, ‘of the whole English people except that part which was under Danish rule’” (Wickham, p 457). The total unification of England will come about in the tenth century, so stay tuned.

“By 900 a new political map had emerged which was to remain unchanged in its essentials until 1453, consisting of an increasingly fragmented commonwealth of Islam, the Rome which we call Byzantium, and the kingdoms of the west,” (Holmes, p 57).

Thoughts?? Did I leave anything out? I’d love for this to be a conversation. So please comment below.

RESOURCES & FURTHER READING

Bishop, Morris. The Middle Ages

Cantor, Norman. The Civilization of the Middle Ages

Hindley, Geoffrey. The Anglo-Saxons: The Beginnings of the English Nation

Hollister, C. Warren. Medieval Europe: A Short History

Holmes, George. The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe

Jarman, Cat. River Kings

Jones, Dan. Powers & Thrones: A New History of the Middle Ages

Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium, The Early Centuries

Samuels, Charlie. Timeline of the Middle Ages

Wallace-Hadrill, J.M. The Barbarian West, The Early Middle Ages, AD 400-1000

Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome

Wise-Bauer, Susan. The History of the Medieval World

Please Note: Some of the copies I used are older publications I found at my local library. These links take you to the most recent edition found on Amazon. So my page references might be incorrect, just FYI. Sorry!

Amazing. Fascinating. Seems to read smoother then early centuries, but i got lost in the byzantine Shenanigans. Worried about the author. Do you have all these people living in your head?

It's just impressive.

Thank you for this, very interesting, all of it. The only aspect of which I had any prior knowledge is feudalism - and that mainly from Alan MacFarlane’s Origins of English Infividualism. He characterised English feudalism as being based on “contract not status” (it was the other way round on the continent), and was primarily a way of holding land. As you say, in return for working the Lord’s land two days a week (a sort of tax rate between 30 and 40 per cent, not unlike today). Lots of customary rights, as well, overlooked by the Blackadder school of history. So much for me, thank you for your much better informed and resourced accounts!