This century seemed a little more daunting. There were multiple players introduced, teams formed and then reformed…and then reformed again. Alliances made. Coalitions built. Then they would all change again. And that’s just with the barbarians. I haven’t even begun to talk about the Christian Church. Whew, my head hurts just typing this paragraph.

SETTING THE SCENE

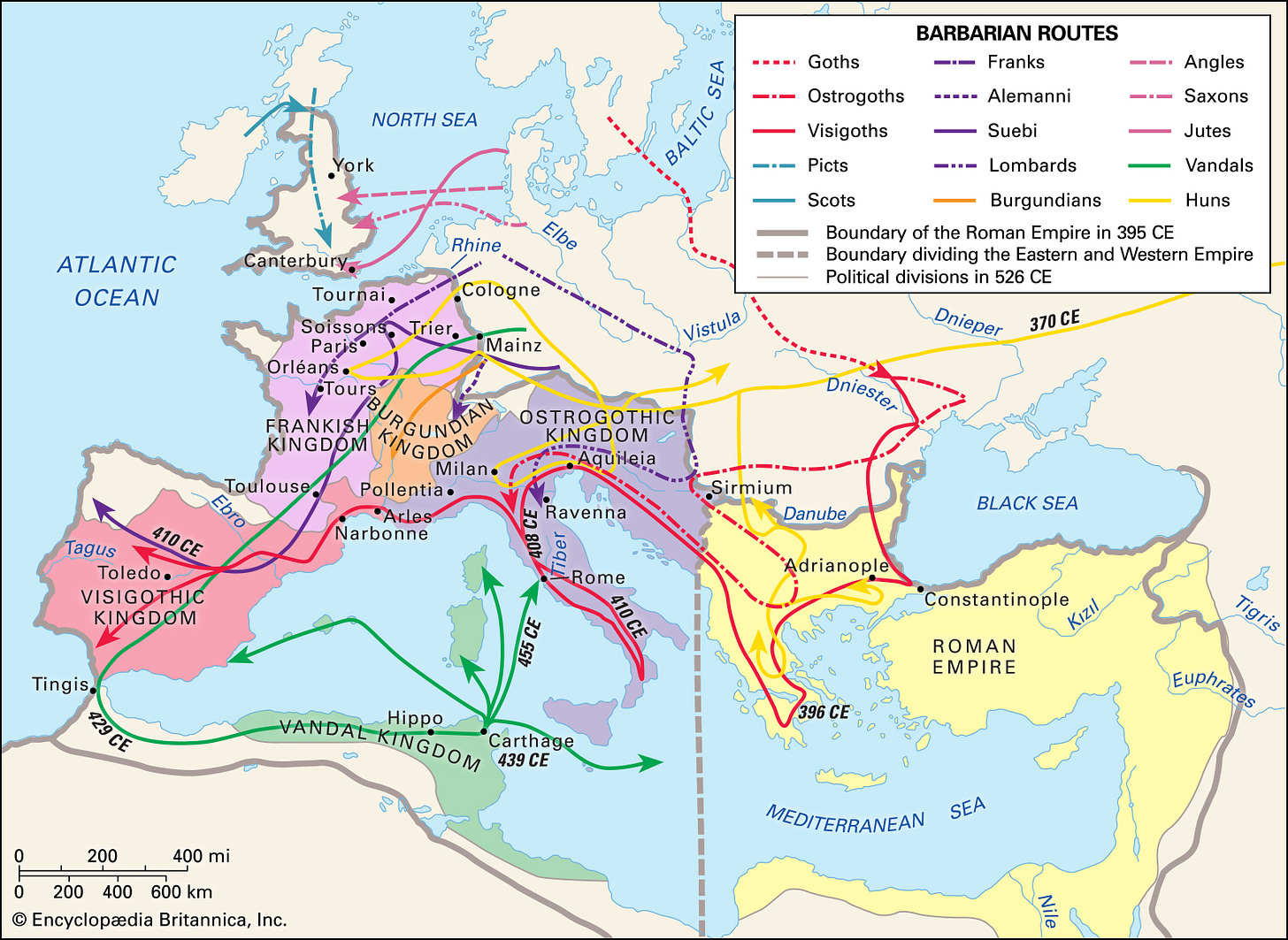

We left off last month at the end of the fourth century. The Roman Empire had split into two. The western half was slowly waning in power and influence. Not obsolete, but in its final act. Comparatively, the eastern half was thriving, but also struggling in certain aspects. From now on, we’ll refer to it as the Byzantine Empire, simply for distinction, but they continued to identify themselves as the Roman Empire. The Christian Church was growing in strength and influence, learning to flex its muscles not only with spiritual matters, but within the political sphere as well. And let’s not forget the mass migrations of people flooding onto the map. Where were they going, you wonder? Well…essentially…everywhere. Further down is a map of their movements and my eyes get crossed if I look at it for too long.

KEY PLAYERS

First and foremost, the two main players of the fifth century were the Christian Church and the barbarians. Although, the label “barbarian” was no longer adequate. The fifth century was all about these seemingly nameless tribes forming little nations by migrating, trying to settle within the Roman Empire, becoming discontent by maltreatment, rebelling, and claiming territory where they would declare themselves a kingdom. Their names would become the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Burgundians, Seuvi, Alemanni, Salian Franks, and so forth.

It’s important to note they did not give themselves these names. Rather, they were given these identities through a term we call “ethnogenesis.” Ethnogenesis is a fictitious ethnic invention, or a birth of an ethnicity. In the case of the barbarians, their fictitious kinship and ethnicity was given to them by the Romans to distinguish who was attacking the empire from where. Eventually, as they began to settle and form kingdoms they would claim these ethnic identities for themselves. But many of these gothic/germanic nations/kingdoms were a coalition of different tribes whose alliances were built out of necessity and similar goals.

Then there was the Christian Church. Oy-vay. Where to begin? Christianity was still spreading and the church was gaining influence both in the east and west. As the Roman Empire withdrew in the west, the church and its monasteries replaced it as the glue that held society together, becoming a strong and steady force people looked to as the violent chaos of birthing kingdoms exploded around them. Through pious gifts of land, the church became extremely wealthy and took its place as part of the landowning aristocracy, further entrenching its power and authority. Meanwhile, the leaders of the church were causing all sorts of internal strife that trickled down to touch everyone, even the common peasant. I’ll get to this in a minute.

Briefly, let’s discuss Attila and the Huns. Because you can’t discuss the fifth century without including them. By the mid century, their influence was felt from the Black Sea to Northern Italy. Dan Jones describes Attila and the effect the Huns had better than I could. He states, “This was the short-lived but disruptive kingdom of Attila the Hun. A genuinely larger-than-life character whose name remains notorious today, Attila took command of the Huns in the mid-430s. And in two decades of his reign, he dragged the western Roman Empire yet further along its path to ruin” (Jones, p. 60). They displaced multiple germanic groups and were a rather irritating thorn in the Roman Empire’s side. But just as quickly as they seemed to appear, they disappeared. Attila came, he conquered, then he died violently in his bed on his wedding night choking on his own blood supposedly from a nose bleed (history…you don’t have to make this stuff up, it actually happens dramatically like this). After his death, the Huns disbanded and dissolved into history.

NOTABLES

The first half of the fifth century saw a lot of movement by different germanic groups. Coalitions of disgruntled peoples formed and attacked territories throughout the waning western empire. Many of these groups had initially entered the Roman Empire as fedoerati, hired mercenaries for the roman army, and were promised land to settle in exchange for their service. But they felt the empire never delivered on their end of the bargain. Thus, these groups rebelled, attacked, and plundered, taking what they believed they were owed.

One pivotal example was in 410 CE, when a coalition of Goths called the Visigoths, led by their self-declared king Alaric, sacked Rome, the Eternal City of the Roman Empire. It was a huge blow to the Roman psyche. An ebenezer of sorts to the empire’s demise in the west.

Alaric was a barbarian who had fought in the Roman army for years. He had hoped to become a general at one point, but was passed over because of his barbarian blood. He would never be seen as a true Roman citizen, no matter how hard or long he fought for them. So Alaric claimed his rag tag army of barbarians for himself, declared himself King of the Visigoths, and began raiding Roman provinces. They were the first official gothic nation to be birthed out of the barbarian migrations. The Visigoths eventually settled and established their kingdom in Southern Gaul (modern day France) and remained a steady presence for several centuries.

Another Germanic tribe that shook the Roman Empire was the Vandals, led by their king Geiseric. The Vandals moved throughout Western Europe, but eventually moved down to North Africa. They took the Roman port city of Hippo in 430 CE and Carthage in 431 CE. These were two major blows to the empire who was dependent on the grain supply from Africa. Essentially the Vandals cut off trading and took over the Mediterranean Sea.

The second half of the century saw more of these groups finding their places. It was no longer an issue of migration into the Roman Empire, but one of claiming territory, establishing their own kingdoms, and defining borders. Different groups settled all throughout the former Roman provinces. Some of the more well-known and successful groups were the Angles and Saxons in Britain (who started seriously invading and settling around the 450s CE), the Salian Franks in northern Gaul, the Visigoths in southern Gaul and Iberia (modern day Spain), the Ostrogoths in Italy, and the Vandals in North Africa. I could do so much more on the barbarians migrations and kingdoms. They’re fascinating to me.

While the barbarians were fighting their way through the realm in search of new homelands, the Christian Church was busy laying its foundations in medieval society and culture. As I’ve mentioned before, there was a power vacuum of sorts when the Roman administration and military presence slowly withdrew from the west. The Church quickly slid into their place and established themselves as the authority to look to, becoming the heart of the few urban cities. Monasteries were also growing in popularity and became economic centers in medieval society which had predominantly returned to an agrarian rural lifestyle. As the intellectualism declined along with the waning roman presence, the monasteries became the bastions of classical learning and literacy.

But it wasn’t such a seamless transition of power and authority. The Church was struggling with two main issues. The first was all about who was in charge and who had authority over the others (it was a pissing contest amongst clergy essentially). The second was about doctrinal disagreements. There were differing views on the nature of Christ and people were having to decide which team they were on.

In 444 CE, the bishop Leo I, declared the bishops in Rome were the highest authority in the entire Church and had the power to make final decisions for all of Christendom. He insisted the Church had supremacy even over the state when it came to spiritual matters. The emperor Valentinian III agreed to this and made it official. As you can imagine, the bishops of other large cities, such as Alexandria and Constantinople, didn’t think this was a good idea. Consequently, they all began excommunicating each other. This also contributed to the constant struggle between popes and monarchs, which was a constant issue throughout the Middle Ages.

A few years down the road, this struggle for authority came to a head in the midst of a doctrinal issue addressed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE. Bishops were arguing over who’s version of Christ’s nature was orthodox…again. There was Team Monophysitism and Team Nestorians. The former believed Christ’s nature was only divine and not human. Hence, the term monophysitism. The Nestorians believed Christ’s nature was two separate persons, divine and human, but functioning together. The council actually declared both were heretical, reasserted the Nicene Creed (declared at the Council of Niceae in 325 CE), and went on to tackle some ecclesiastical housekeeping, including declaring the Bishop of Constantinople was second only to the Pope of Rome. John Norwich describes it as, “From this moment was born the ecclesiastical rivalry between the Old Rome and the New which was to grow increasingly bitter over the centuries until, just 600 years later, it was to erupt into schism” (Norwich, p. 157).

Why am I going into this, you ask? It’s important to be aware of the debates occurring within the church. Religion in the Middle Ages was an integral component of everyday life for everyone. It permeated all spheres of life; not just spiritual, but also political, social, financial, even military. These controversies and arguments created major schisms (think Eastern Orthodox Church breaking from Western Catholic Church) and were the beginnings of ongoing theological debates about doctrine and church authority (think Protestant versus Catholic, the Reformation, and so on). All of this affected not just monarchs and governments, but trickled down to the normal guy too. It would be folly to dismiss the spiritual and religious when learning about the Middle Ages.

AS FAR AS I CAN TELL…

So the century was rife with barbarian migrations, the births of new Gothic kingdoms, constant religious controversies, and the death of the western Roman Empire. Yes, let’s not forget the death of an empire as a major notable.

As we’ve seen, the empire was slowly dying in the west. And in 476 CE, a barbarian named Odoacer finally administered the coup de grace and swung the inevitable deathblow. Once again, him and his gothic mercenaries had not been given what they believed they deserved for their service. So Odoacer marched his army toward Ravenna, where the child emperor Romulus Augustus sat. They defeated the Roman army, captured and imprisoned the emperor, and Odoacer declared himself King of Italy. And that is how the sun set on the western Roman Empire for the last time. Some claim this date, the fourth of September 476 CE, as the end of the Western Roman Empire and thus the beginning of the Middle Ages. But of course, this is debated. I’ll continue to mention the different dates proposed each month as we pass them on our timeline.

As the Germanic tribes settled and established their new kingdoms, the remaining Roman population was demoralized with heavy taxation, loss of Roman citizenship (for some), and no protection. As Dorothy once said, “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.” The Western Roman Empire was a thing of the past. Now, they were in barbarian country. I love how Susan Wise Bauer sums it up, “But the death warrant for the western empire had been signed by Constantine over a century before, when he had decided that Romanness alone could hold the empire together. Odovacer’s rise to the throne of Italy was merely the final admission of what had already happened: the barbarians had given up on the project of becoming Roman” (Wise Bauer, p. 138).

So the barbarians gave up trying to become a part of the Roman Empire. However, the Barbarian kingdoms didn’t replace the empire, but emerged as heirs of the Roman Empire. This is not my original idea, but a popular one. For more on this, please read Chris Wickham’s book The Inheritance of Rome. They occupied the vacancies of power the empire had left in its wake. But their kingdoms saw a blending of the two forces, Germanic and Roman, in their culture, law, administration, and governance. And of course, Christianity influenced things heavily as well. Most of the barbarians were Christian, a heretical sect called Arian, but Christian nonetheless. And the savvy leaders soon realized the importance in allying with the Christian Church for legitimacy, power, and influence in the realm…which we will see in the next century.

MAIN RESOURCES & FURTHER READING

Bauer, Susan Wise. The History of the Medieval World

Bishop, Morris. The Middle Ages

Cantor, Norman. The Civilization of the Middle Ages

Gombrich, E. H. A Little History of the World

Hollister, C. Warren. Medieval Europe: A Short History

Holmes, George. The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe

Jones, Dan. Powers & Thrones: A New History of the Middle Ages

Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium, The Early Centuries

Samuels, Charlie. Timeline of the Middle Ages

Wallace-Hadrill, J.M. The Barbarian West, The Early Middle Ages, AD 400-1000

Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome

Please Note: Some of the copies I used are older publications I found at my local library. These links take you to the most recent edition found on Amazon. So my page references might be incorrect, just FYI. Sorry!