If you remember, we wrapped up the ninth century with this…

By 900 a new political map had emerged which was to remain unchanged in its essentials until 1453, consisting of an increasingly fragmented commonwealth of Islam, the Rome which we call Byzantium, and the kingdoms of the west. (Holmes, 57).

The 10th century is famous for “the birth of Europe,” due to this newly formed political map. But it also had so much more to offer, there was more to it than just that. I’m pretty sure no one in the 10th century was looking around considering how their institutions/states would define and carry through to the next millennium. I think of the decline of the Western Roman Empire. People still identified themselves as Roman and part of the empire. They didn’t see the delineation we do. They would have been confused if someone had time traveled and asked them their thoughts on “the collapse of the Roman Empire.” I believe it was the same for “the birth of Europe,” I’m not even sure 10th-century folk even used the term “Europe.”

So when researching, I asked myself what the 10th century was all about if we didn’t impose a focus on finding the “birth of Europe.” Below is what I found.

SETTING THE SCENE

We start the 10th century with a decentralization of power, fragmented states and empires, and authority and influence held by localized states and wealthy families. A lot of this can be attributed to the Viking invasions, which led to Francia being fragmented with a plethora of duchies and other local and regional units weakening the French throne. The Viking invasions would also unify England. Simultaneously, further east, the invasions of the Magyars allowed the burgeoning German state to rise into its preeminent place. It’s also important to point out the 10th century was in the middle of the Medieval Warming Period (MWP), a time when the increase in temperatures led to a boost in food production and more tolerant climates for living.

KEY PLAYERS

BYZANTINE EMPIRE

This was the Byzantine Empire’s great age of expansion and reconquest, notably in the eastern frontier, Italy, and parts of the Balkans (Holmes, 176). They were also able to expand into Arab-held territory. The aristocracy in the eastern marshlands who knew the terrain well, built wealthy military dynasties, gaining power and influence through their wealth and the holding of political offices, creating instability for the empire (Holmes, 177). These military fortunes allowed for a widespread cultural renaissance that could be seen in the restoration of icons (which flourished once the empire settled the iconoclast controversy by adhering to the Eastern Orthodox side of the argument). It seems the Byzantine Empire was on the up and up again (at least in some ways). However, some sources had nothing nice to say about it. Cantor used a demeaning tone toward Byzantium, adhering to the nineteenth-century scholars’ label of being an “atrophied civilization” that added nothing in the way of ideas, technology, science, or medicine, only in art. “The task to which the Byzantines dedicated themselves was merely one of preserving the satisfactory and comfortable existence they had inherited,” (Cantor 227).

ISLAMIC EMPIRE

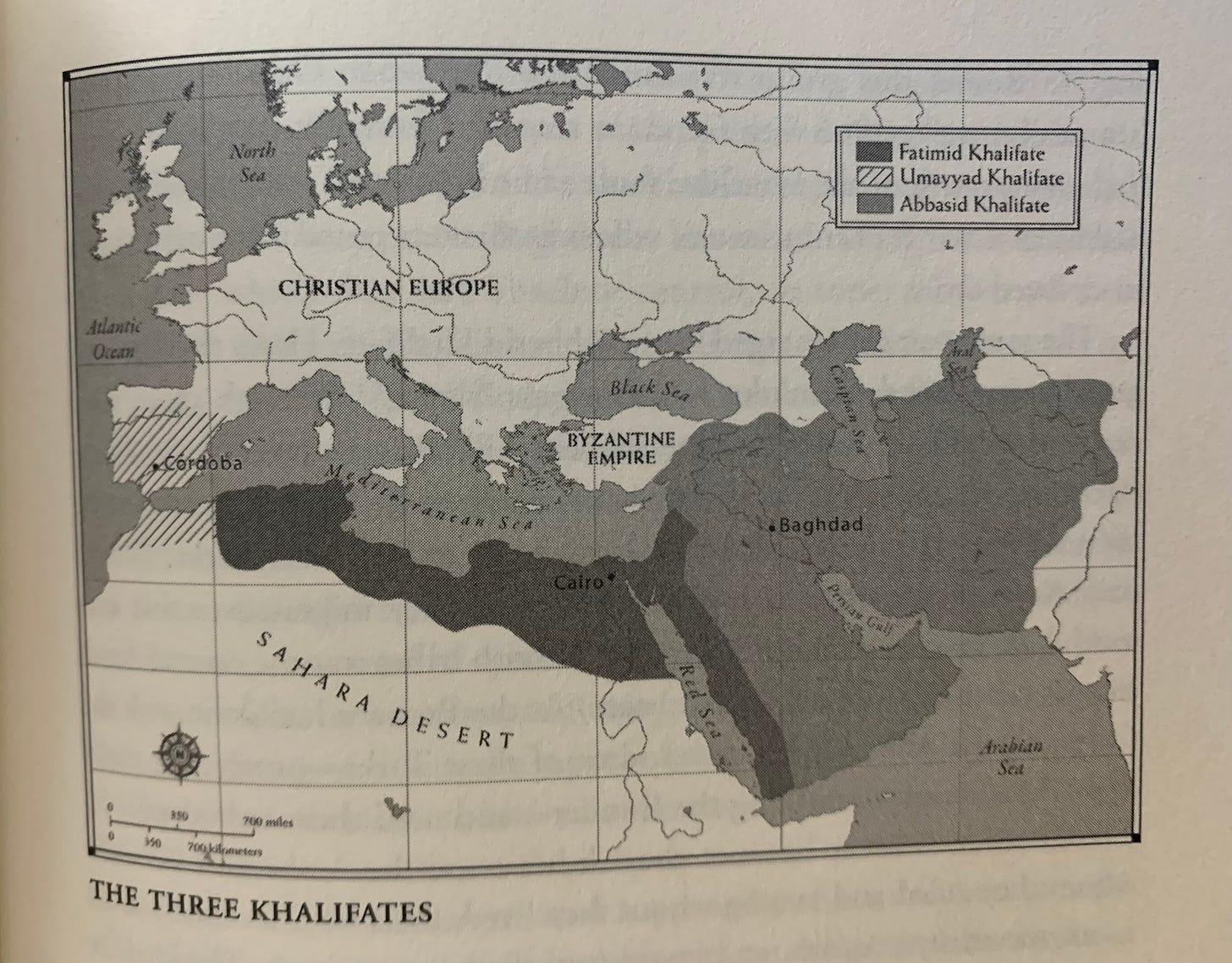

Over the course of the century, the Islamic empire divided itself into a Muslim tripod of sorts, its legs being the Abbassids in Baghdad, the Fatimids in Egypt, and the Umayyad Caliphate in Cordoba. Yet, in spite of the fragmentation and instability, this was still considered the Islamic Golden Age. Confusing, I know.

In the east, rival groups fought for control of the state, and regional commanders who became de facto rulers of their own disintegrated the unity of the Abbasid caliphate (Holmes, 184). The Abbasids went bankrupt due to these independent Muslim states refusing to send tribute and taxes, and struggled to hold onto power (Holmes, 183).

Down in Egypt, another famous Islamic dynasty rose in power, the Fatimid family. Established when “Shi’i warriors from Tunisia seized control of Egypt and declared themselves the true khalifas of Islam. They had the resources of North Africa and the granaries of the Nile valley to draw upon,” (Ansary, 120). They founded their capital in Cairo in 969 CE, which became a major Mediterranean powerhouse. The Fatimid caliphate was the most successful, richest, and most stable of the 10th-century Muslim states (Wickham, 336-8). They also built the world’s first university in Cairo, Al Azhar, which is still there today!

Then west, in Al-Andulus (Spain) the Umayyad caliphate ruled from their capital in Cordoba, which was the largest city in Western Europe at the time (Collins, 198). “A visitor in 950 described it saying it had “no equal in Maghrib, and hardly in Egypt, Syria or Mesopotamia, for the size of its population, its extent, the space occupied by its markets, the cleanliness of its streets, the architecture of its mosques, the number of its bath and caravanserais,” (Collins, 198). Starting in 929 CE, Abd al-Rahman III was the caliph of Cordoba, ruling Spain and Morocco. He beautified the Great Mosque and made international trade flourish (McKitterick, 55). He expanded his territory both North and South and improved the agricultural economy and trading networks (mainly increasing the slave trade by being the conduit between Frankish, Anglo-Saxon, Irish, and Slavonic slaves into the Middle East) (Collins, 191). In 936 CE, he began building a massive marble palace called Madinat al-Zahra in the Sierra Mountains. His successor, his son al-Hakim II, is famous for building a magnificent library. Al-Andulus excelled at the sciences and cosmology and produced some of Islam’s greatest mathematicians, geographers, and astronomers. For example, Maslamah al-Majriti (a mathematician and astronomer), Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Zarqali (a great astronomer), and Mohamed Abul-Quasim Ibn Hawqal (a geographer) (Collins, 199).

There is so much more I could share about the Islamic Empire and its Golden Age, but I don’t have time here. I want to discuss Sufism, the position of women in Muslim culture and society, the Mamluks (Abbasid khalifate’s imperial guard built entirely of slaves), and the Persian family the Buyids (whose story sounds like the Merovingian “Mayors of the Palace” we’ve studied previously). Please go read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes by Tamim Ansary. I’ve really enjoyed reading his book.

WESTERN/LATIN CHRISTENDOM

There is so much to cover. Let’s start east and work our way west.

It might sound like deja vu, but circa 900 CE a “pagan tribal people who had migrated toward Central Europe from the east, to settle the vast plains that spread out from the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. They were skilled riders who fought with bows and arrows from the saddle,” (Jones, 225). These were the infamous Magyars. They implemented planned raids, took over established trade routes and gained significant wealth (McKitterick, 71). It’s not a perfect parallel to the Huns, however. The Magyars were decisively defeated by the Germans at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 CE, eventually settled, and converted to Christianity. A once nomadic pagan people became another part of Latin Christendom. The Magyar ruler, Stephen I, invited missionaries and built dioceses of the Catholic church, so the Pope responded by crowning him king in 1000 CE, effectively establishing the Kingdom of Hungary.

Next on the map is the German state…errr, by the end of the century, the German Empire…Holy Roman Empire, to be exact. In the beginning, though, it was mainly dominated by five duchies which could have remained on top, except for the Hungarian invasions and the new German monarchy that rose in dynastic proportions (Hollister, 124). In 919 CE, Henry I, a duke of Saxony was elected to the throne by the other German dukes. He established the Ottonian dynasty. But it was his son, Otto I (936-73) who is credited with creating the famous German monarchy, because he insisted on being crowned by the archbishop in Aachen (remember this place…Charlemagne’s old capital?), a not-so-subtle move positioning himself as the successor of the great emperor (Cantor, 212). He was putting the whole theocratic monarchical rule thing to use. It strengthened the symbiotic relationship between ruler and church, legitimated himself above the other dukes and in return gave protection for the church against the nobility, gave rich endowments for ecclesiastical establishments, and allowed churchmen to be placed in royal political positions (Cantor, 213). Otto I subdued the other dukes, victoriously defeated the Magyars and married an Italian queen setting himself up to take the crown from the Lombards. Then he traveled to Rome where the pope crowned him emperor. Even though his empire was distinctly German it was strongly associated with the old Roman Empire (Hollister, 125). His crowning was known as renovation imperil Romanorum, ‘the renewal of the Roman Empire’ (Holmes, 187). Collins claims that out of the chaos, the Ottonian dynasty restored order by converting the Saxons and establishing an effective working central government (Collins, 5). There is also the Ottonian Renaissance to be mindful of, where abbeys and nunneries became hubs for learning and literary production (Hollister, 128). Of note is Roswith of Gandersheim, a nun in Saxony who became the earliest major female poet of the Middle Ages and the earliest post-Roman European playwright of either sex (Hollister, 125). Look her up!

Italy’s claim to fame for the 10th century was its cities, especially its port cities. While local upstarts were feuding and grabbing for the throne, maintaining the fragmentation and decentralization of the state, the Church grew more influential and the cities grew prosperous through trade. The Italian kings gave power and privilege to the bishops in their cities to repel Magyar and Muslim invaders. Eventually, these bishops had complete control of the cities’ defenses, as well as their revenues and courts of justice (Hollister, 131). Genoa, Pisa, and Venice were formidable commercial centers and hubs for trade with a strong merchant class, able to repel the Byzantine and Muslim domination of the Mediterranean. Venice was the first state to live by trade alone. A Lombard wrote, “These people neither plow nor sow nor gather grapes, but buy grain and wine in every marketplace,” (Hollister, 132).

In Francia, it seems the two big key players were the Normans and the famous Cluny Abbey. What they had in common is similar to what was happening in the German realm: a fusion of church and state that built order out of the previous century’s chaos. In 911 CE, a Viking named Rollo was granted land in Western Francia by the French king Charles the Simple in exchange for a cease of his attacks. Rollo and his men immediately converted to Christianity. Rollo changed his name to Robert I and began operating his new domain completely independent of the French king. By the end of the 10th century, Robert’s descendants held extensive territories and had forged the Duchy of Normandy. It became the strongest state in Europe west of the Rhine (Cantor, 207). In the 980s, they played kingmakers by helping place Hugh Capet on the French throne, replacing the Carolingians. And as smart 10th-century rulers did, they built a strategic partnership with the Church, bringing in monastic scholars to improve the Norman church. They built monasteries and supported monastic schools, establishing thriving hubs of learning similar to those in Ottonian Germany (Cantor, 208). We’ll see much more of these Normans in the 11th century when they decide to take a nearby island for themselves. In the rest of Francia, the other great feudal princes and duchies we saw last century continued to rule their little fiefdoms independent of the ineffectual Carolingians or Capetians on the throne. I’ll discuss Cluny Abbey in a minute.

For now, let’s move west to the British Isles. First of all, if you want a fantastic historical fiction series about England in the 10th century please read Bernard Cornwall’s The Last Kingdom. The 10th century starts with the death of Alfred the Great, leaving his son Edward on the throne. Edward successfully teamed up with his formidable sister Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, and they enjoyed some amazing victories. “The royal team of siblings, the Lady Aethelflaed and King Edward, made a logical division of labour. She looked after the western frontiers against the Welsh and the northwest against the incursions of Irish Vikings via Chesire and Lancashire while at the same time making probing attacks into the northern Danelaw beyond Watling Street. Edward combated the Danish warlord kings in East Anglia and the East Midlands with the aim of extending West Saxon hegemony in those regions,” (Hindley, 267). If Edward “established” England, then his son Athelstan (who took over in 924 CE) turned England into a lasting reality (Collins, 215). Athelstan’s greatest achievement was his decisive victory against the Vikings and a coalition of the kings of Scotland, York, and Dublin in 937 CE at the famous Battle of Brunanburgh. The Vikings were stopped and the Celts were confined to Scotland and Wales (Collins, 216). By the mid-900s, all of England was united under the kingdom of Wessex, and from 955-980 CE, there was relative peace and prosperity (Hollister, 116). But in 980 CE, Viking raids resumed. The king, Ethelred the Unready, made a dire decision to placate the Vikings by paying them off, thus establishing the Danegeld (dire, because the Vikings realized it was more profitable to get paid off than to raid, so they kept coming back and demanding more each time). Collins claims Ethelred’s rule and this decision was the beginning of the end for Anglo-Saxon England (Collins, 222).

NOTABLES

A notable attraction of the 10th century was the Christian church’s spread and evolution. It seeped into every nook and cranny on the Western European map. Not only did most people convert around this time, but the church permeated politics, solidifying its influence for at least a millennium to come. Again, not only that, but the monastic world presumably was one of the primary driving forces behind an intellectual and artistic awakening.

I’ve mentioned it above, but there was a symbiotic relationship between the Latin Church and the Ottonian state, and the Norman duchy that was fully realized in the 10th century. The concept had been tried before—remember St. Boniface crowning the Merovingians—but this century’s attempt seemed to be more successful. Cantor called it a “medieval equilibrium” between ecclesia and mundus (Cantor, 218). Collins said that “Europe shared a common ecclesiastical-political ethos held together by a Catholicism that cut across linguistic and national boundaries,” (Collins, 5). However, this new situation for the Church wasn’t all rainbows and cupcakes…errr, purity and piety? “The papacy in this period reached levels of viciousness and depravity that certainly exceeded the corruption and excesses of the renaissance popes,” (Collins, 7). Again, for the sake of time, I will simply encourage you to look up sæculum obscurum, or the Pornocracy, for more details on why this century was considered the “Dark Ages” for the papacy.

The monastic world seemed to fair better than the papacy. It was the Golden Age of Monasticism (Jones, 208). A monastic boom occurred with the Benedictines, the Cistercians, Carthusians, Premonstratensians, Trinitarians, Gilbertines, Augustinians, Paulines, Celestines, Dominicans, and Franciscans, as well as military orders that included the Templars, Hospitallers, and Teutonic Knights (Jones, 194). But the most influential one was the famous Cluny Abbey, a Benedictine monastery established in 910 CE in Burgundy by the Duke of Aquitaine. By the end of the century, it was the leading monastery in Europe that led a powerful and influential network of other monasteries. Its success was due to its immunity from both lay and episcopal interference. It was only subject to the papacy—which, if you remember was a bit distracted in Rome with its own depravity and corruption—thus freeing the monks to run their community on their own (Cantor, 219). It had a church that rivaled the Hagia Sophia, a world-class library and artistic center and was home to a prestigious community of religious men (Jones, 195). It gained massive wealth and influence by being the headquarters of hundreds of “daughter” houses all over Europe that answered only to the abbot of Cluny (Jones, 194). Dan Jones called them the spiritual McDonalds because they could be found everywhere, ha!

Another important notable of the 10th century were women! I stumbled across so many fascinating stories of formidable women living lives and dominating in roles I would have thought impossible in the early Middle Ages. For example, did you know there were female Viking warriors? A Danish historian said…

There were once women among the Danes who dressed themselves to look like men, and devoted almost every instance of their lives to the pursuit of war…for they abhorred dainty living, and used to harden their minds and bodies with toil and endurance…they put away the softness and light-mindedness of women, and inured their women’s spirit to masculine ruthlessness…these women offered war rather than kisses, and would rather taste blood than bussess… (Jarman, 145-6).

Look up the Birka Female Warrior to learn more. Then there was Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, possibly the only woman from Anglo-Saxon England known to have led military forces (Jarman, 144). Then Gerberga of Saxony, the sister of Otto I of Germany, organized the defense of Leon in northern France in 945-6 when her husband, Louis IV, was captured (Jarman, 144). These were two women who had the ability to lead military strategy and forces with the support of their contemporaries (Jarman, 144). Also, please research Freydis Eiriksdottir, a Viking who traveled to North America several times, commanding the boat of men herself (please note some don’t think she was a real person, so read with a grain of salt). Or look up Theophano, wife of Otto II, who co-ruled with her husband and became the empress-regent for her son. She was an integral link connecting the Byzantine Empire with the nouveau Holy Roman Empire. Or Otto II’s mother, Empress Adelheid, and his sister Abbess Mathilda of Quedlinburg. Or Marozia’s dominance in Rome. “This was a time when strong and talented women had an opportunity to exercise real power,” (Collins, 275). These women and their stories do not paint an accurate picture of the average woman of the 10th century. They were definitely exceptions to the rule, but fascinating nonetheless.

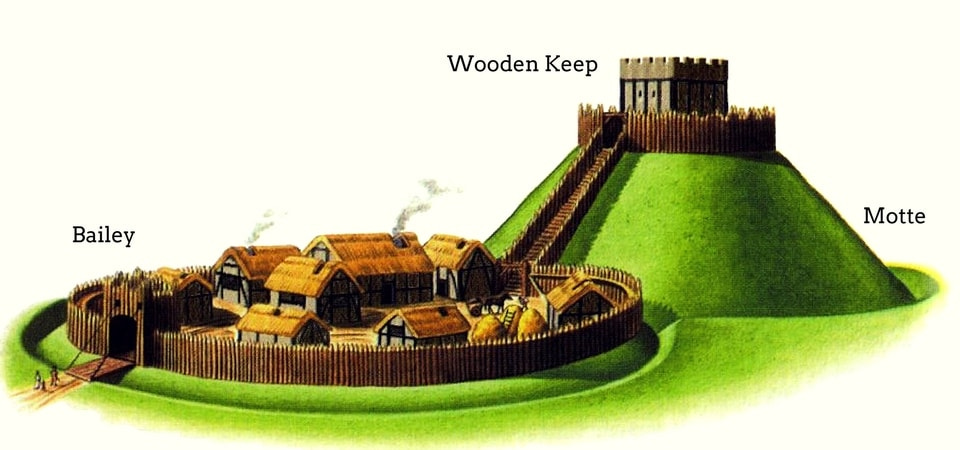

Two more characters of the 10th century to highlight are knights and castles! Because why would we even study the Middle Ages if we didn’t include these?! Within the multitude of duchies in Francia, there were smaller estates of lords who lacked titles but still had considerable authority and resources. These landowners were called “nobles” and were responsible for maintaining peace and order and could wage war against outsiders and each other. Each of these noble households had a military, a group of vassals, which came to be known as knights. These knights were trained in mounted combat and exempt from agricultural work. At this time in the origin of the famous knight, they didn’t own land, but this would evolve and change soon (Hollister, 118-120). “From the tenth century, the status and importance of knights rocketed across the medieval West. Within a couple of generations, Frankish-style heavy calvary evolved to become preeminent on battlefields from the British Isles to Egypt and the Middle East” (Jones, 229). Dan Jones has an excellent chapter entirely devoted to the establishment and evolution of knights in his book Powers & Thrones. Another military innovation of the 10th century was the castle, which at this point in time were just small square towers encircled by wooden stockades, but powerful tools of defense and territorial control (Hollister, 120). “The coming of castles changed the character of the aristocracy by giving great families a specifically located center of power,” (Hollister, 120). These were known as Motte-Bailey Castles.

AS FAR AS I CAN TELL…

The 10th century was really about the strengthening of the bonds between rulers and the church. This symbiotic relationship was a pillar of the Middle Ages. It allowed for cohesion within states which countered (but not fully replaced) the fragmentation so prevalent at the beginning of the century (this can especially be seen in Ottonian Germany, the Duchy of Normandy, the formation of Hungary, and other states that fused with Latin Christendom through the conversion of its people). “Ecclesiastical and secular political ideas, leadership, and resources were inextricably joined together in the creation and progress of these states,” (Cantor, 205).

All of this, coupled with the MWP and engineering developments (for example, the horse collar and stirrup improving transportation and watermills developed to grind grain and increase food supply) allowed people a moment of reprieve from focusing solely on survival and look to the improvement of their quality of living (Cantor, 228). Perhaps this is why we also see a re-awakening of the intellectual and artistic mind, which can be seen in the Golden Age of Islam, the Golden Age of Monasticism, and the Ottonian Renaissance. Just a conjecture, I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Peter Heather, a scholar and historian whose area of expertise is the early Middle Ages, says that…

by the tenth century, networks of economic, political and cultural contact were stretching right across the territory between the Atlantic and the Volga, and from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. This turned what had previously been a highly fragmented landscape, marked by massive disparities of development and widespread non-connection at the birth of Christ, into a zone united by significant levels of interaction…Trade networks, religious culture, modes of government, even patterns of arable exploitation: all were generating noticeable commonalities right across the European landscape by the end of the millennium (Heather, 611-12).

Because of this, I can see the emphasis on “the birth of Europe” being attributed to the 10th century and considered the main take away. But from my research, the 10th century held so much more. My two additional takeaways would be the crystallization of the symbiotic relationship between church and state and the intellectual and artistic re-awakening of the medieval mind. What are your thoughts? Anything you’d like to add or contest?

RESOURCES & FURTHER READING

Ansary, Tamim. Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

Cantor, Norman. The Civilization of the Middle Ages

Collins, Paul. The Birth of the West: Rome, Germany, France, and the Creation of Europe in the Tenth Century

Heather, Peter. Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe

Hindley, Geoffrey. The Anglo-Saxons: The Beginnings of the English Nation

Hollister, C. Warren. Medieval Europe: A Short History

Holmes, George. The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe

Jarman, Cat. River Kings

Jones, Dan. Powers & Thrones: A New History of the Middle Ages

McKitterick, Rosamund. Atlas of the Medieval World

Price, Neil. Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings

Stafford, Pauline. “Powerful Women in the Early Middle Ages: Queens and Abbesses,” Chapter 23 In The Medieval World, 418–435. Routledge, 2002.

Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome

Wise-Bauer, Susan. The History of the Medieval World

Online Articles:

Hudson, Alison; British Library. “How Was the Kingdom of England Formed”

Medievalists.net. “The Women Who Ruled the Papacy.”

Please Note: Some of the copies I used are older publications I found at my local library. These links take you to the most recent edition found on Amazon. So my page references might be incorrect, just FYI. Sorry!